October 31, 2017.

- Many fintech companies these days are being built to be licensed or sold to banks, but the industry hasn't had a bank go on a fintech buying spree yet

- Banks that buy fintech startups don't acquire their earnings, which means they need to be a uniquely perfect business fit -- but that's hard to find.

Written by Tanaya Macheel,Michael Deleon,Zoe Murphy,Tearsheet Editors,Zack Miller Originally published at this link.

Tearsheet’s one-day “Hot Topic :- Mobile Payments” event is coming up in NYC on Nov. 30 and we’re opening up a few complimentary spots to executives from banks and other financial institutions to attend. Interested? Apply here.

Banks always say to stay relevant among fintech startups they have to build, buy or partner with them — but most of them have been “partnering” and few have been buying. Two weeks ago, JPMorgan Chase acquired WePay, a small business-focused payments company. In the last three years, Silicon Valley Bank acquired Standard Treasury, BBVA acquired Simple, Ally acquired TradeKing.

That’s it.

Compare that with the amount of money invested in companies. According to CB Insights data, Citi has invested in about 25 fintech companies since 2012 and Goldman Sachs in 23. Outside of banks, venture capitalists have thrown almost $55 million behind fintech startups in the same period, strategically planning the best exits as young companies seek to partner or be acquired. As a result, more and more, fintech companies are looking less like companies and more like products waiting to be sold.

“From a personnel perspective there hasn’t been a lot of attention, at least from banks’ corporate development teams, in structuring themselves to invest and understand how fintech companies might fit into their operations,” said Matt Wong, lead intelligence analyst at CB Insights. “You’re starting to see that change a little bit.”

Banks have poured millions of dollars into fintech companies over the past five years, but outright acquisitions of fintech companies by banks are still pretty rare — a function of the fact that they don’t often come by platforms that fit into their existing business models and the ones that promise sure-fire returns don’t just grow on trees.

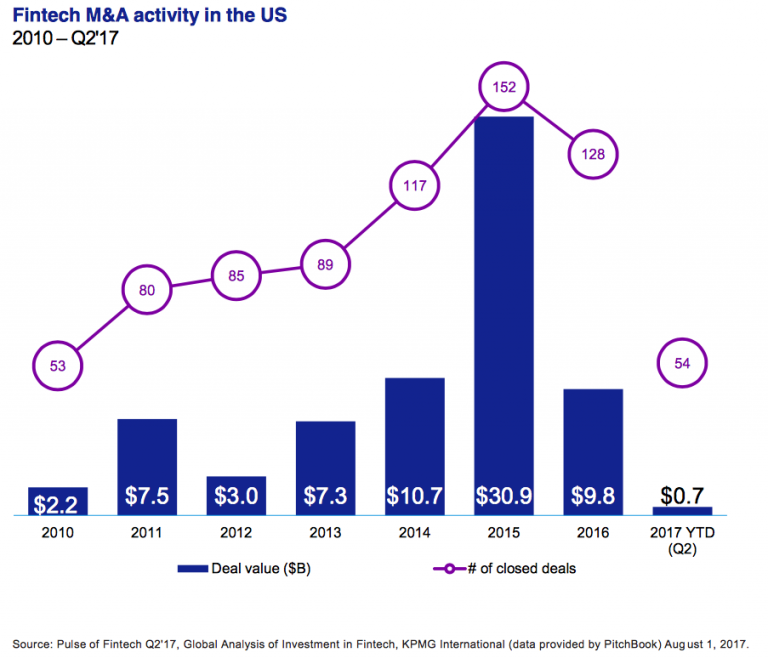

Fintech mergers in general have also been on the decline since 2015.

Banks aren’t trying to be major fintech investors, though, said Sam Yildirim, the deals leader at PwC. They’re just looking for technology they can use in their existing business that’s sophisticated enough to fully bring in-house, instead of having to build it themselves.

“They’re looking for unique opportunities to acquire platforms that will add to their growth rather than changing their business model. Banks are not technology companies,” she said, contrary to how banks like to tout themselves. “It takes too long for them to build technology themselves.”

That’s perhaps one reason why banks prefer to interact with fintech startups as vendors rather than move them in completely: they don’t plan to change their business models. Most fintech companies and products were created with the idea that they might upend the traditional financial system, and a lot of what the industry has learned — especially from the use of open APIs — is that in order to keep up, banks need to look to platforms as business models, not just tech constructs.

People in financial services often talk about the platformification of banking as a whole, but Wong pointed out that that conversation is especially applicable to a very small number of banks — like Goldman Sachs, which actually seems to be moving toward a platform model.

A recent CB Insights teardown of jobs listings at Goldman Sachs showed almost half of openings were in technology (and many of those in digital finance specifically). Goldman’s acquisitions seem to be mainly motivated by the need to acquire tech talent into its employee base, Wong said.

By planning and structuring acquisitions that way, the bank has been able to bring tech talent without going through the formal acquisition process.

“From a regulatory compliance perspective, fintech startups might be doing things that just might make it difficult for banks to consider them” for a potential acquisition, Wong said. Typically, fintech companies are mostly goodwill; they want to help people manage their finances more effectively, make saving money invisible or teach people how to invest — things that don’t necessarily promise a strong return on equity, Wong said.

It’s hard to collect data on bank-fintech acquisitions. CB Insights hasn’t put together an exact figure on how many banks have made acquistions. PwC’s Yildirim also said it’s hard to make a numbers-based assessment because there’s “not enough transparency” and that there’s “lots of data but it’s not clean.”

“When you look at the significance of those transactions, they’re minor, they’re tiny,” she said.

Terms of the Chase-WePay weren’t disclosed but the bank is rumored to have paid at least $220 million for it. A “small deal” is considered $250 million or below, according to a recently published PwC study.

“The purchase price is often not disclosed. These fintech companies are growing fast but they may have negative earnings and may not generate positive cash flows yet. What you’re acquiring from the platform is not necessarily the earnings of the company.”